No other people have had a more dominant impact on the modern wine world than the British, but to understand how an island nation who couldn’t grow decent wine influenced how we all drink, you have to first look back to the country’s time under Roman rule. By 43 AD, when Rome conquered Britain, the Empire had already stormed across Europe, capturing France and the city of Bordeaux as another one of its prizes. Seeing Bordeaux as a strategic port due to its location, Rome used the city to facilitate trade with its new province, illustrating the strategic and economic benefits the city of Bordeaux had to offer to its northern neighbor. Hundreds of years later, the British would remember Bordeaux and its wine as they would use its port to serve as the linchpin for creating the modern wine industry.

The Global Wine Trade Begins – In Bordeaux

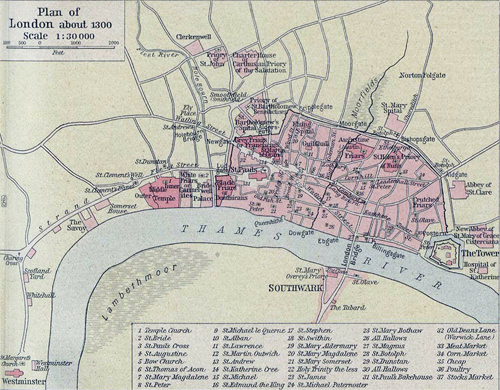

French King Louis VII divorced Eleanor of Aquitaine in March of 1152 and by May she was married to Henry, the Duke of Normandy, who two years later inherited the English throne. The Duchy of Aquitaine, which Eleanor had ruled and included the region of Bordeaux, now belonged to the English crown. Politics, geography and marriage thus led to Bordeaux becoming the cheapest source of wine in Britain. The city’s winegrowers were granted preferential tariffs, leading to an export boom and by the 1300s, hundreds of ships, often traveling together in massive fleets, were ferrying a quarter of the city’s wine north to London – amounting to nearly 30 million modern-day wine bottles.

The wine business in Bordeaux is unique in that middlemen called négociants sit between the winemakers and importers who purchase wine in bulk. The négociants set the price and thereby influence the winemakers. But by the 1300s, the British merchants had grown so important, that they began to influence the négociants. Many British merchants took things a step further and became négociants themselves, allowing them to buy directly from the vineyards. These merchants shipped the wine they purchased back to London, where they sold it to everyone from the royal family to poor citizens in taverns. As the largest group of drinkers of Bordeaux wines, the tastes of the British dictated the style, which they took to calling claret (initially clairet). These thin, sour wines tasted nothing like the wines we drink today, and were in fact made very differently, using spices and other flavorings to appeal to the palette. The modern claret we know today would only come about in the seventeenth century, after the Dutch drained the swamps of the Medoc, creating ideal conditions to grow high quality wine.

Before that all happened though, the Hundred Years’ War, fought on and off from 1337 to 1453, would put a temporary end to British demand for Bordeaux wine. The Bordelais continued to grow wine for the next 200 years, but little of it left the city, and even less found its way to Britain. Bordeaux and Britain would rekindle their love affair after the war, but for the time being the British needed to find somewhere else to feed their wine habit.

The British Look Elsewhere For Their Wine

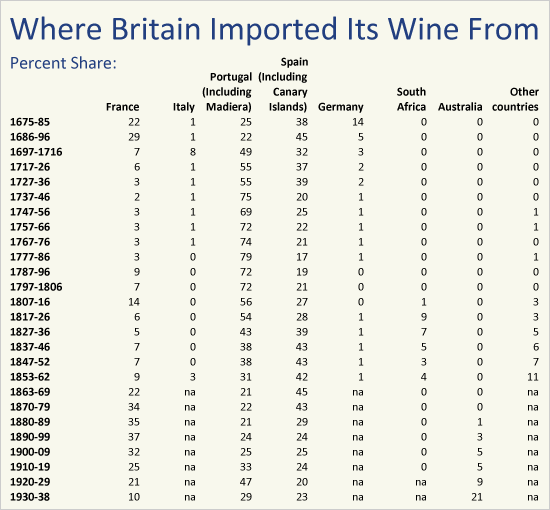

Port, which is a fortified red wine produced in Portugal’s Duoro region, also has the British – along with an earthquake – to thank for its mainstream success. In 1703, while at war with the French (among other countries during the War of the Spanish Succession), Britain entered into the Methuen Treaty with Portugal. This treaty included a provision stipulating that the tariff on wine imported from Portugal would be a third less than that imported from France. As British demand for Portuguese wine soared, British merchants migrated to Porto in order to cut their costs.

Lisbon, Portugal’s capital and largest city suffered massive damage in 1755, when one of the deadliest earthquakes in recorded history struck the city. A year later, as part of an effort to finance the rebuilding efforts, the Duoro Wine Company was established, monopolizing the Port business in government hands. British merchants began to work closely with the government monopoly. Exports of Port to Britain rose as the country embraced fortified wine, which actually improved during its voyage to London. This attracted more British merchants, who built lodges across the Duoro River, in Vila Nova de Gaia, where they aged Port in wooden barrels. It was during this period that Port’s production method evolved. In the past, neutral spirits were added to the casks of wine after fermentation; doing so produced a wine that could survive the voyage at sea, but not a particularly appealing one. Adding the spirits to the wine during fermentation instead, killed the yeast before they finished their work, leaving a large quantity of residual sugar. This resulted in a high alcohol wine that was sweet and smooth.

During the first half of the eighteenth century, Port had little to recommend it but its cheapness, but, during the second half of the same century, both the price and the quality of Port were raised gradually, with the result that the popularity of the wine, as shown by the figures relating to imports, increased steadily until the superiority of Port over all other wines became part and parcel to the creed of every true-born and true-hearted Englishman.

– Andre L. Simon’s In Vino Veritas

This pervasive British influence can still be seen today in the decidedly English-sounding names of many of Port’s prominent ‘houses’ such as Cockburn, Graham, Osborne, and Taylor.

The Age Of Exploration – Fueled By Fortified Wine

As the British Empire emerged, spreading across the globe, fortified wine grew in prominence. Absent modern preservation techniques, sealed glass bottles in particular, wine quickly spoiled. The sailors on merchant ships needed something to drink, and fortified wine fulfilled that role. Madeira, a Portuguese island, was perfectly positioned to serve the ships that plied the Atlantic trade routes. The island’s winemakers began to fortify their wines in the sixteenth century, to better serve the export market the Age of Exploration had created. These wines grew in popularity as the sailors of the day realized that the wines improved in quality the farther they traveled, due to the constant heat and movement (which have the opposite effects on regular wines).

While Dutch merchants were large purchasers of Madeira, the fortified wine found its most devoted followers in the British colonies of North America. Madeira was considered by many early Americans (former British colonists) to be America’s first national beverage, albeit an imported one.

The British also played a prominent role in the modern evolution of Sherry, a fortified white wine from Jerez, Spain. The name Sherry itself is a corruption of Jerez, the city where the wine is grown. The British were exposed to Sherry in the early sixteenth century during a period when French wine imports were interrupted by war. The drink captured the nation’s attention again in 1587, following Sir Francis Drake’s successful raid on the shipyards were the Spanish were building their famed Armada. While his forces were burning as many of the ships as they could in Cádiz, they managed to recover a good bit of Sherry that had been intended for export elsewhere.

Ironically, it was a temporary loss of the ability to export Sherry to Britain (along with the Netherlands) that led to the creation of the Sherry that we know today. What we call the solera system began to be practiced by Sherry producers accidentally. Rather than intentionally blending together different vintages, merchants did so out of necessity as demand was low and casks needed to be topped off from time to time. The merchants, many of them hailing from England and France, discovered that this practice markedly improved Sherry’s flavor profile. Sherry exploded in popularity when the British market reopened to the Spanish in the middle of the nineteenth century. Dry and sweet styles appealed to different segments of the British population, creating massive demand. Some have estimated that by the mid 1860s, Sherry accounted for over 40% of the wine Britain imported.

Marsala, Sicily’s fortified wine, is yet another fortified wine that owes its global success to the British. In 1773, a British merchant named John Woodhouse is widely credited as being the first person to fortify with spirits the wines being grown around the city of Marsala. He named the fortified wine after the city of Marsala and shipped it back to Britain where it was well received. By 1796, British demand was such that Woodhouse decided to establish his own facilities in the city of Marsala, which led to greater production and commercialization of the beverage.

Seeding The New World

As Britain began to establish colonies across the globe, the colonists brought their taste for wine along with them. In fact, two of the largest wine-producing countries in the world, both former British colonies, owe their success to the work of a single British citizen — James Busby. While the First Fleet carried vine cuttings (picked up in South Africa) to Australia in 1788, early efforts to grow wine saw little success. It wasn’t until 1824 when Busby migrated to Australia that things began to change. Initially he taught viticulture, but the school where he had been posted to soon closed. Busby persisted, however, bouncing from post to post, and publishing two books on viticulture. In 1831 he travelled back to Britain, and then took off on a tour of Europe during which he collected hundreds of vine cuttings. He shipped these to Australia, where they were successfully planted and grown. For these efforts, Busby is known as the “father” of Australian wine.

In 1832, Busby’s life took an interesting turn, when the British government appointed him to the post of British Resident of New Zealand. Through a number of political twists and turns involving the native Maori and the French, he helped bring New Zealand under formal British control. While living in New Zealand he continued to pursue his passion for wine and planted the nation’s first vineyard. It was this vineyard that proved wine could successfully grow on the island and an industry would emerge from the revelation.

Solidifying Influence On The Modern Wine Industry

There is no modern wine industry without the glass bottle, and while humans have produced and drank wine for over 8,000 years, the wines we drink today are dramatically different than their historical ancestors. Much of this has to do with the ability to properly store wine so that it doesn’t spoil due to oxygen exposure. The glass bottle was the answer to that problem.

While the British neither invented glass bottles, nor were the first to store wine in them, it was a company in Bristol called Rickets that figured out how to mass produce wine bottles. In 1821, Rickets received a patent on the machine that performed this feat, though selling wine by the bottle remained illegal in Britain until 1860 for reasons dating back to the seventeenth century. In 1860 the British government also reduced tariffs on French wine, creating a match made in heaven – the ability to buy bottled wine at a cheaper price – that helped to kick off a 15 year “golden age” of French wine, which saw production reach the equivalent of over 1 billion bottles a year. If not for this “golden era,” French wine might not be at the level of importance it is today. The “golden era” came to a crashing halt though when phylloxera wiped out vineyards across the country. French wine would eventually recover, however, aided by phylloxera resistant rootstock imported from Britain’s former colony across the Atlantic.

…

Today, after centuries of influencing the development of the modern wine industry, wine is finally flourishing in Britain itself. Production is still relatively small, but some see a much larger future for English, Welsh and even Scottish wine. In an ironic twist, geography, which played a pivotal role in so many of Britain’s historical interventions, is at heart of these predictions. If climate changes bring about warmer summers many believe that vines may thrive in England and Wales, and as far north as Scotland. Time will tell.

Sources

Inventing Wine – Paul Lukacs

The Oxford Companion to Wine – Jancis Robinson

Wine Politics – Tyler Colman

Note: For simplicity’s sake we have referred to England and the English as Britain and the British at certain points where it is not historically appropriate.

Images via Shutterstock.com