What if you could order a side of social justice with your half-price IPA at Happy Hour? Your local watering hole may shed more light on cultural trends than you think. Throughout history, there are some interesting parallels between our favorite bar tradition and women’s fight for equal rights.

“Happy Hour” initially had little to do with alcohol. In fact, it didn’t even originate on land but at sea. During World War I, the term referred to wrestling matches and similar revelry aboard naval ships. Instead of being a welcome lull from a busy work week, Happy Hour was an active break from a monotonous daily routine.

Meanwhile, first-wave feminism was well underway. History recap: Various countries around the world granted women voting and other rights long before America did. Even in the United States, suffragettes had already fought for and won women’s right to vote in certain states in 1912. In 1920, the 19th Amendment guaranteed voting rights to women nationwide.

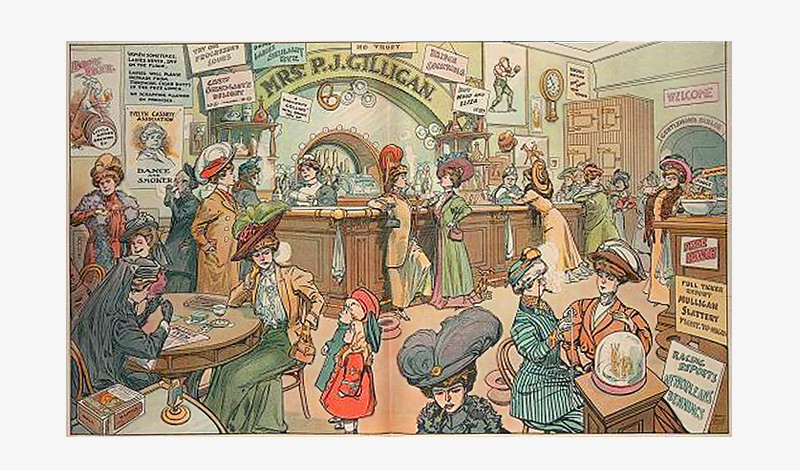

But suffragettes weren’t only concerned with voting. Their fight was about securing a variety of basic legal rights for women and breaking into certain male-dominated spaces. In that fight, bars became a symbolic battleground. A 1908 illustration by Harry Grant Dart for Puck magazine shows a “horrifying” scene of a bar full of women; they’re smoking and drinking and generally having fun in ways that only men were “allowed” to (nowadays, that bar just looks awesome).

The slang term “Happy Hour” caught on with folks on land in the Prohibition years of the ‘20s and ‘30s. The idea of a little programmed rowdiness must have sounded attractive. “Happy Hour” was a handy code to talk about kicking back at a speakeasy pub, without admitting publicly to violating Prohibition. Speakeasies were among the first venues where women could claim a spot alongside men at the bar, as well as the voting booth.

Second-wave feminism in the 1960s through the ‘80s brought women a new focus: work. Don Draper may be the star of “Mad Men,” but women were also rushing back to work in droves. New inventions like the birth control pill made it easier to put pregnancy on hold for a career. Major feminist writers like Simone de Beauvoir and Betty Friedan were publishing books galvanizing women with arguments against old-fashioned mores, like the belief that a woman’s place is at home.

With the workforce expanding this way, it’s no surprise that bartenders took note. Happy Hour as a social respite after the grueling workday gained popularity in America in the ‘60s. It’s hard to imagine that women didn’t affect a popular cultural rebranding of Happy Hour. Whether bars catered to all workers who needed a break from the rat race or even to men who could no longer count on a 1950s housewife to prepare cocktails at home, women undoubtedly played their role.

It’s also important to note that certain bars were laying critical groundwork for the next wave of feminism. Third-wave feminists in the ‘90s are often officially credited with introducing intersectionality, with more attention on issues of sexuality and race. But this view doesn’t take into account that queer women, trans women, and WOC were doing important work long before mainstream (i.e., white) feminism took notice.

The Stonewall riots that kicked off the modern gay rights movement happened in 1969 at the Stonewall Inn — in other words, at a bar. Even before this monumental event, gay rights advocates organized “sip-in” protests at bars, and gay bars were important sites for community-building between people who were often forced to the margins. By 1993, New York magazine reports, “legions of fashionable gay women” on the bar scene even gave rise to a “lesbian chic” trend in mainstream circles.

In addition to more mainstream feminist attention to intersectional feminist issues, third-wave feminists were increasingly concerned with gender violence issues like rape culture and sexual harassment.

In terms of bar life, news features on the dangers of “date rape” drugs led to legislation banning the use of Rohypnol (a tranquilizer used in roofies). Getting a drink was newly seen as a potentially dangerous act for women. What seemed like a terrifying step backward at the time did have a silver lining. The public image of rape had been the stranger dragging a woman into an alley. The dark side of bar life forced everyday people and state attorneys general to confront the idea that an attractive guy on a first date could also be a rapist. New guidelines for police and college campuses began to address these more common forms of assault.

This brings us to today. It’s always hardest to define the historical moment that you’re currently living in. Modern, or “fourth-wave” feminism is still evolving. One of the key characteristics, however, is a move toward social media and other online activism. The interesting thing is that bars have come along for the ride.

One weapon some bars have found to fight rape culture is social media’s power to go viral. Offering a coded “secret menu” women can order if they need help feels like a genius callback to speakeasy passwords. In this case, instead of granting access to a secret bar, requesting an “angel shot” could be code for a bartender to summon a bouncer, a getaway cab, or even the police. The power of online sharing works better than word of mouth to alert women to bars that have their backs, and inspires other establishments to do the same. Gender equality isn’t a reality yet, but feminists of all genders can find ways to enjoy a Happy Hour special and stand up for justice at the same time.

On its surface, Happy Hour is about cheap pitchers and delicious, greasy food. Look a little deeper, and a more complex mirror of social achievements and concerns may appear. If you want to know what issues are on the table, you might want to start by asking the women and the barflies.